- YouTube link to the English version

- IMDB page for the English version

-  Russian Wikipedia page for Цареубийца

- Â Kino Reticulator’s Ward No. 6 blog entry.

-  Палата №6 at kino-teatr.ru

Unfortunately I couldn’t make today’s May Day parade in Moscow, but I did something even better. I re-watched the May Day parade in Mne Dvadtsat Let (1965). I don’t usually like being part of a crowd or parade, but I can’t help but enjoy this one.

It’s great fun, partly because of all the people-watching opportunities. Marlen Khutsiev filmed it at as part of an actual May Day celebration, so the crowd consists of a lot more than professional actors.

This isn’t the only place where Khutsiev used this technique of placing scenes in the context of actual public events. A couple that come to mind are a poetry reading (in the same film) and a reception for foreign ambassadors (July Rain). But this is one that makes me go, “How’d he do that?” May Day comes only once a year, so he had only one chance to get it right, but he blended the film with the actual street scenes very well. The sound track does a lot to tie things together, but the sound track couldn’t do it all by itself.

Anyhow, there is a lot to watch – the people in the crowds, and the filmmaker’s technique, as well as our hero Sergei and his new friend Anya. Sergei finally got to meet her at the celebration, after having followed her home, at a distance, after seeing her on a tramcar the previous year. (The tramcar scene is the subject of an earlier post, Twentysomething Lost in Books.)

Here are screenshots to help others join in the spirit of the celebration (I hope). Maybe even more helpful would be to watch the scene on YouTube, even though that version doesn’t have English subtitles. The parade starts at 50:20.

The celebration finally comes to an end, and later in the film Sergei and his two male friends, as well as Sergei and Anya, start to drift apart.  The issues that came between them were not entirely unlike issues that were confronting young people in the United States as the 50s turned into the 60s. The film was released in 1965 but was mostly filmed several years earlier. The delay was partly due to Khrushchev denouncing it, prompting Khutsiev to make some changes.  I’ve long wished I could see the version that Khrushchev denounced, before Khutsiev made his changes, but maybe it doesn’t exist anywhere.  This article at Kinoeye (Being 20, 40 Years Later) provides a little more detail about what happened than I’ve read elsewhere.

This film and Khutsiev’s next one, Iulskii Dozhd (July Rain) are two that sometimes make me think the world of the Soviet Union of the late 50s-early 60s is more familiar to me than the United States in the 2010s. For me they are high impact films – especially July Rain. Strangely, I’ve yet to meet anyone from Russia, either online or in person, who has seen July Rain, and I’m not sure I’ve even met anyone who even heard about it. These films did not endear Khutsiev to the Soviet authorities, so they weren’t seen by many people back at the time. And I’m not sure they would have quite the same impact on younger people, anyway. So maybe there is nobody to talk to about them.

Here’s the IMDB link for Mne Dvadtsat Let.

In this scene from “Vory v Zakone†(1988), the corrupt procurator looks quickly in his law book and then tells the would-be complainant, “Sorry, but unfortunately there is no help here.” (Or something like that. I cannot follow the full conversation.) He’s obviously not a lawyer getting paid by the hour if he can make the determination that quickly, or maybe the Soviet laws were extremely clear and accessible if he could dispose of an issue that quickly. But what really caught my attention was the book cover.  The title was clearly shown just before the procurator closed the book in a show of sad resignation, thus enabling me to google for it.

Here it is: Soviet Law and the Citizen. You can buy your own set (there are two volumes) at ozon.ru.

One of my first reactions to the movie scene was to ask how people could respect the law if it has a book cover like that? That looks like a high school textbook from the 60s.

Here is an earlier version of Soviet Law and the Citizen. It’s more dignified, but still…

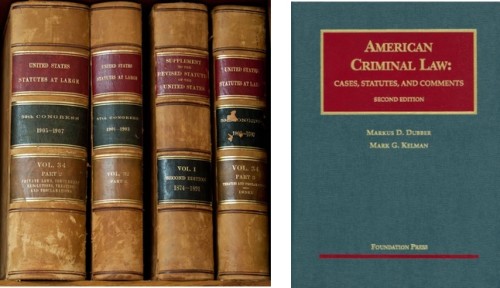

If you want people to respect the law, it needs to be bound in books like this. They lend gravitas and a sense of historical weight.

On the other hand, maybe historical weight is exactly what the Soviet government did not want, considering its type of revolutionary history.

I don’t know exactly what kind of effect the publisher of these laws was trying for, but one thing I’d wager is that any symbolism or connotation was intentional. So much of our own court system is intended to make an impression on the people — the architecture, the spacing and positioning of the courtroom elements, the judicial robes. It’s fun to look at Soviet movies (as well as photos in news articles about modern Russian court proceedings) and compare the two systems and speculate on what kind of effect each was intended to have on the participants. Since there are quite a few Russian movies with court scenes, this could be the subject of several blog articles to come.

I’m not sure what the filmmakers were thinking of when they made this car chase scene in “Vory v Zakone†(1988). Gangster #1 (played by Valentin Gaft) has his driver take off at high speed after Gangster #2, who tries to get away.

I’m not sure what the filmmakers were thinking of when they made this car chase scene in “Vory v Zakone†(1988). Gangster #1 (played by Valentin Gaft) has his driver take off at high speed after Gangster #2, who tries to get away.

Gangster #1’s girlfriend, Rita, was in his car when he started, so after getting up to speed he stops the car to interrupt the pursuit and let her out, tell her he loves her (in none-too-speedy a fashion) and then resume the chase.

Gangster #1’s girlfriend, Rita, was in his car when he started, so after getting up to speed he stops the car to interrupt the pursuit and let her out, tell her he loves her (in none-too-speedy a fashion) and then resume the chase.

Amazingly,Gangster #2 didn’t use the interruption to lose Gangster #1, because immediately thereafter Gangster Gaft sans girlfriend is is still on his tail, and the usual sort of mahem ensues (including running over a baby in a carriage).

Amazingly,Gangster #2 didn’t use the interruption to lose Gangster #1, because immediately thereafter Gangster Gaft sans girlfriend is is still on his tail, and the usual sort of mahem ensues (including running over a baby in a carriage).

This wasn’t a slow-speed comedy chase like the one in Eldar Ryazanov’s “Beware the Car.â€

Maybe the explanation is in parts I couldn’t understand, which is a lot of them.

Rita (played by Anna Vladlenovna Samokhina) later betrays Gaft’s gangster character, but I don’t think it’s in revenge for such an awkwardly-put-together scene.

I wonder if this 1988 film was the first of the long run of violent Russian gangster movies about the post-Soviet days, mostly tiresome ones. I can’t think of an earlier one of this genre.

The title can be literally translated as “Thieves in Law.â€Â I gather from the Wikipedia Article, “Thief in Law,†that this title phrase itself goes back a lot further than the modern gangster/mafia-type days. (The “talk†page is perhaps more interesting and informative than the article itself.) Given the role of the militia and procurator in the film, I thought it might in this case be referring to the corrupt entanglement of the police/legal system and the criminal establishment outside the prison system, even though the original “Thief in Law†phrase seems to have referred to criminals within the prison system.

It looks like it has been two years since I posted anything here. I’m still watching Russian films, though. The pace of film watching has slowed down the past couple of years, but in the past couple of weeks I’ve been looking for films that have both English and Russian subtitles, so I can put them on my smartphone to watch while running on the elliptical machine.

A few weeks ago I found the MX Player for Android app, which allows me to put two sets of subtitles on the screen at once. What’s more, I can enlarge the font size to fill up most of the screen space and make them easy to read while I’m in motion. So now I’m looking for films to make use of these features. Until yesterday I had only two: Dvenadsat (12) and Evil Spirit of Yambuy (Zloy Dukh Yambuya).

The scene pictured above comes early in Khrustalyov, My Car! (ХруÑталёв, машину!). This, however, is not one of the films for which I’ve found both Russian and English subtitles. But looking for subtitles for this one led me to www.subtitleseeker.com. There I’ve found English subtitles for it, and have been finding both Russian and English subtitles for a handful of other Russian movies. I don’t know why I never found that site before, but it’s turning out to be very helpful.

Back to Khrustalyov, My Car! Without subtitles I could make no sense of it. The spoken Russian is not very clear. People speak in disjointed fragments or talk over each other. When they’re not mumbling they speak in screeches and squawks. It’s all against a cacophonous background of coughing, spitting, wheezing, belching, and weird mouth noises. I don’t recall any sneezing, though. I’ll have to watch again to see for sure. It quiets down somewhat at Stalin’s deathbed, but he doesn’t go without a few bodily orifice noises of his own.

So it’s not the best movie for language-learning. Even with English subtitles, I couldn’t make much sense of it. These two reviews helped, though:

I’ll watch it again, but now that I found a good subtitle site I’ll be spending more time with some old films that have both English and Russian subtitles.

Even though he no longer speaks, we watch inmate Dr. Ragin (played by Vladimir Ilin) very carefully to get an idea of his current mental condition, wondering just how aware he is of what’s going on. He’s an inmate in the hospital that he used to run. Nice touch, given the clues we get from the way he eats.  And the ominous, omnipresent Nikita watches, too. And watches us, as well.

Even though he no longer speaks, we watch inmate Dr. Ragin (played by Vladimir Ilin) very carefully to get an idea of his current mental condition, wondering just how aware he is of what’s going on. He’s an inmate in the hospital that he used to run. Nice touch, given the clues we get from the way he eats.  And the ominous, omnipresent Nikita watches, too. And watches us, as well.

I wondered if this scene was in the Chekhov short story that the film is based on, so went to read it here (in English translation). I learned that this scene was not in the original, but even so, the film is remarkably faithful to the original story.

Movies based on books (or a short story, in this case) usually depart so far from it as to be unrecognizable (and so shallow as to be unworthy of the original) or follow it so closely as to be incoherent to one who has not read the original.  American films usually fall into the first category, and Russian films sometimes fall into the second.  But there are some Russian films that are worthy film adaptions of the original.  After reading the story I will state that this film is not only good on its own, but honors the original remarkably well.

There is not much on IMDB about Палата â„–6 (Ward No.6). It’s a 2009 film. It was directed by Alexandr Gornovsky and Karen Shakhnazarov.  I’ve recently watched Shakhnazarov’s Rider named Death, which was good, too, but am otherwise not familiar with his work.

Screenwriter Aleksandr Borodyanskiy did Rider named Death (based on a novel) as well as this one. And Afonya. Maybe I should learn more about his work.  I see that he was born in Vorkuta in 1944. That’s enough to make him interesting already.

It’s not a spoiler to tell about the ending of a 37-year-old movie, is it?

I don’t know if this is one of those movie lines that made its way into popular culture in Russia, but it’s certainly one that has stuck in my mind (after doing a LOL the first time I heard it).

Afonya is being questioned by a nice young militia (police) officer.  He had been sleeping in the grass, and his passport and plane ticket showed that he was picking destinations almost at random.   “From what we running?” asks the nice young officer.  “From myself,” mumbles Afonya.

Which is a true enough answer, even if it’s psychobabble.  The reply: “From yourself you can run, but not from the militia.  Come with me.”

I suppose you had to have been there.

Judging by the films Afonya (1975) and Autumn Marathon (1979), Georgi Daneliya had not yet broken free of the constraints of socialist realism in 1975.  He was still working within that box, mostly, but on the other hand the box was not boxing him in.  The values of collective society are explicitly stressed over those the individual, but the story is about an individual, Borshev, and is at least as much about his self-destructive behavior as his society-destructive behavior.

In fact, the scenes in which he is put in front of the collective for some labor discipline elicit more sympathy for Borshev, the individual, than for the collective. And this is even though we’ve seen what kind of slacker and self-server he can be.  Most of the workers are portrayed as being bored or tired of these proceedings, and are inclined to make a joke of them.  The box is a pretty battered container by the time Daneliya is done with it.

There are only the faintest echoes of the theme of collective over the individual in Autumn Marathon. There is no labor discipline, but there is a scene (pictured here) that demonstrates how intellectuals were kept under control.   (Some might say the method in this scene is not all that different from the way conformity is maintained within the American university system, or even that it’s a more subtle technique than we have.)  But this scene just demonstrates another way in which the main character, Buzykin, is helpless to change his life.   He can not bring himself to do anything to resolve the conflicting demands of his wife and girlfriend, and cannot do anything to make himself stand up for right treatment of his colleagues, or even avoid complicity in ill-treatment.

In Afony the individual does manage to reform himself, or get reformed by others, although there is some ambiguity on that point.  In Autumn Marathon, nothing changes in the end. There are attempts, but to no avail.  But in Marathon, reform for an individual would not have much to do with conformity to society.  If you’d want to make the point that Buzykin should get his life in order for the good of society, you’d have to make up that part of the story for yourself.  The movie isn’t going to do it for you.

I suppose all of this is debatable.  As usual, I probably miss a lot of subtleties and cultural allusions, given that it’s not my country and not my language.  I also wish I could find an overview on what was happening to the whole concept of socialist realism in Russia the 1970s.   Unfortunately, all of the English-language materials on the subject that I’ve found so far seem to deal with it only through the 1960s, if even that.    So I’m still looking for reading material on the Decline and Fall of socialist realism in Russia.

It bugs me that I can’t remember where else I’ve seen the actor in the white jacket in Afonya.  It was some bit part in a film, just like in this one.

It bugs me that I can’t remember where else I’ve seen the actor in the white jacket in Afonya.  It was some bit part in a film, just like in this one.

It was good to see another Georgi Daneliya film.  So far I’ve seen:

One of these is not like the other four.    The last four have good character studies and have elements of “sad comedy,” a term most often used for Autumn Marathon.   It’s pretty hard to see that in the first one. Of course there were eleven years between I Step through Moscow and Afonya. One wouldn’t expect the full range of talent from a 34-year-old director that would develop later.  But now I’m interested in watching some of the films from that period between 1964 to 1975 to look for clues as to how that talent developed.

By the time Afonya was made it was there.  Good film. I expect it will bear much re-watching. Â

It seems I liked Forgotten Melody for Flute a lot more than the Washington Post reviewer did when the film came out in 1988, during perestroika.  He wrote:

It seems I liked Forgotten Melody for Flute a lot more than the Washington Post reviewer did when the film came out in 1988, during perestroika.  He wrote:

The major attraction of “A Forgotten Tune for the Flute” is its insights into everyday Soviet life. It takes us inside the apartments of privileged bureaucrats and less-well-off nurses and gives us a sense of the Soviet attitude toward cultural reform, careerism and sex. There’s even a glimpse of how Soviet paramedics handle a heart attack emergency. As a glasnost document, it has something of interest to offer; as a movie, it’s a rather drab occasion.

But what kind of movie about life in a bureaucratic system could it be if it was not about drabness?

I’m pretty sure Eldar Ryazanov was well aware of the drabness of deception and careerism, because why else did he intermix it with the occasional scenes of the pure voices of young innocents who he sent off on a tour?

I’m pretty sure Eldar Ryazanov was well aware of the drabness of deception and careerism, because why else did he intermix it with the occasional scenes of the pure voices of young innocents who he sent off on a tour?

The rapt attention of young sailors on an aircraft carrier where the chorus is performing is also a contrast to the everyday corruption that some of the characters back home at the Leisure Time Directorate would occasionally like to escape.

The rapt attention of young sailors on an aircraft carrier where the chorus is performing is also a contrast to the everyday corruption that some of the characters back home at the Leisure Time Directorate would occasionally like to escape.

I think Ryazanov knew what he was doing, and did it well.

I wonder if Tatyana Dogileva considers this the best role she ever had.  From the three other movies in which I’ve seen her I wouldn’t have guessed that she could turn in a nuanced performance like this one.