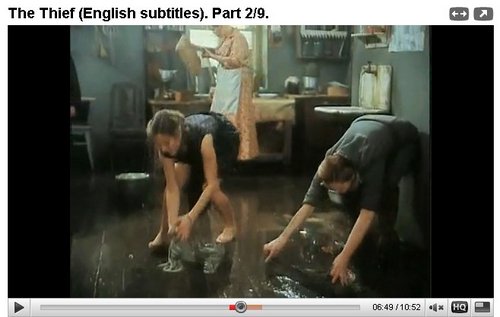

I still don’t know what to call the 2nd category into which I’d put this scene. Up to this point Inna Churikova’s character has always been dressed in 1970s business atire. She has a family life as well as a public life as town mayor, but she has never before put on a housedress. But in this scene she does, puts some stirring traditional music on the turntable and goes to work washing floors. I take it as a sort of getting herself back to the peasant roots of Mother Russia, to inspire some patriotic/nationalistic feeling in herself in order to steel herself for the big task that lies ahead, which is to raise her voice in favor of the building of better apartments for the people of her town.

Without subtitles I wasn’t able to understand nearly as much of this film as I had hoped. But just before this scene, I think I heard her tell her son that “the people need apartments.” And that understanding seems to be supported by some of the other scenes, e.g. where she is on an inspection tour of some of the dangerously defective apartments that people are living in.

I can’t make out Russian cursive writing very well, but I’m guessing the 2nd line of her note her is the title of the movie, which means something like “I wish to speak.”

And this is where she wishes to speak. This may also have been a scene in Siberiade, btw. It seems to be some big plenary session or congress. I presume it would really have taken some courage for a small-town mayor to speak up in that setting.

I’m not really sure about the “peasant” part, btw. Given that a concerted effort was made to eliminate traditional peasants in favor of communal farms during Stalin’s time, I’m not sure if peasant origins were really supposed to represent the traditional nation in the same way that American farms and small towns used to do for us, at least before a lot of people decided they didn’t like Sarah Palin talking about it.

Here is Stirlitz doing something similar in Semnadcat’ mgnovenii vesny. He has been living undercover in Germany for many years, living as a suave and sophisticated German. I’d say he had been eating German food and drinking German beer, but I don’t think any of the tavern scenes shows him with a beer stein. Cognac or wine, maybe. But at this point, one-third of the way through the series, he seems to be steeling himself for the very dangerous work ahead, by inspiring in himself a feeling of nationalism and patriotism. He does it by putting on traditional Russian music, drinking vodka and eating roasted potatoes straight from the ashes of his fireplace, getting his face sooty in the process. I would guess that that, too, takes him back to the peasant origins of Mother Russia, or something like that.

As an outsider it’s easy for me not to understand this very precisely, but it seems that in both films something of the sort is taking place.