Pokayanie has some really strange musical references. Here Yelena breaks into a singing of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy,” in German. The effect is sinister. It comes after she tries to “comfort” Nino by saying the following:

Of course, the arrest of Sandro and Mikhail is a mistake. We must summon up patience, both you and I. You’ll see, Nika will do everything.

They’ll look into it and free them. You must be strong, Nino. Don’t forget that you have Keti. I’m sure it will end well, everything will be all right. They’re bound to find the truth and set Sandro free. I’m sure of it! Nino, I’m thinking now of your girl. Keti must become a good citizen and an honorable woman. Your misfortune must not lead her astray. Don’t forget that we’re serving a great cause. The future generations will be proud of us. But since the scale of events is so grand, big mistakes are inevitable. It may even happen that innocent people are victimized. But I can already hear our favorite “Ode to Joy†by Beethoven which will surely sound all overthe world very soon.

I can almost understand what that music is doing there, because of the totalitarian overtones in Schiller’s poem. I had only a vague idea of what was totalitarian about it, though, so I went to google to see if anyone else ever had the same thoughts. In doing so, I found the following in the book, “Sound matters: essays on the acoustics of modern German culture” By Nora M. Alter, Lutz Peter Koepnick (2004).

It talks about the “Enlightenment project of universal harmony [which] at once needs and loathes the dissonnant in order to define itself. The construction of hegemony through harmony cannot do without separating the world into friend and foe, self and other… “[T]he passage from Schiller’s ‘Ode to Joy,’ in which those who are not accorded all-embracing love are banished from it, involuntarily betrays the truth about the idea of humanity, which is at once totalitarian and particular.”

“At once totalitarian and particular,” it says. If that isn’t a good description of what’s in this movie, I don’t know what is.

But what about the other music? How about that brief showing of partygoers arriving with music and booze, to the accompaniment of Bobby Hebb’s “Sunny.” Is that merely meant to be ironic, given what’s happening? Or am I too dense to catch a deeper meaning?

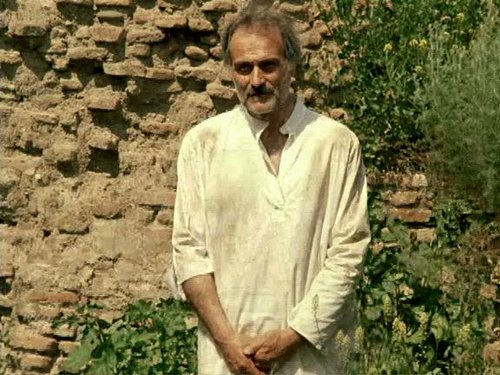

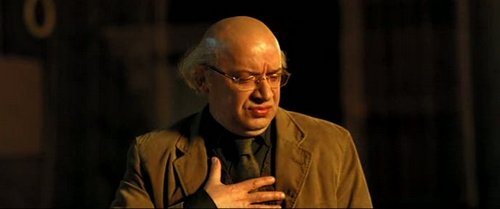

And what about those Italian opera segments sung by Varlam and his flunkies. Those, too, are in a sinister setting. But I don’t recognize them from anywhere, mainly because I’m ignorant about opera. What do they mean?

And what about that Wagner duet on the white piano? I’ll bet there is some meaning to it, but I don’t know what it is.