Yesterday I started reading the 1990 edition of Robert Conquest’s, “The Great Terror.” I had long known about Conquest’s work, but had never read any before.

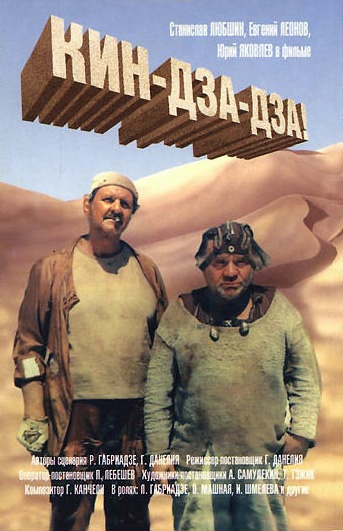

In a way I’m glad I waited until after I watched a lot of Russian movies. Not that Russian movies give an accurate portrayal of life in the Soviet Union any more than American movies give an accurate portrayal of life in our country. But they give me a picture of how the authorities wanted the Revolution to be seen, and (more importantly) of what sort of portrayal the population needed to see in order to be part of it. And now more than ever before, I see all the players as real people.

One thing that’s surprising to me is how much dissent there was in high places in the Communist Party in the late 20s and early 30s. I had known about Mensheviks, and I had known about people like Trotsky, but not about this. Chapter 1, which follows a long chapter of Introduction, tells us, referring to one of the opposition groups that were led by people who had been Stalin’s followers:

They seem to have circulated a memoir criticizing the regime for economic adventurism, stifling the initiative of the workers, and bullying treatment of the people by the Party. Lominadze had referred to the “lordly feudal attitude to the needs of the peasants.”

There is a lot more like that.

In the Introduction there is a good section summarizing the crackdown on the people. It points out that the starvation of perhaps 10 million people, mostly in the Ukraine, was not an accidental byproduct of Moscow-centered economic policies, but a deliberate attempt to show the people who was boss.

There seems little doubt that the main issue was simply crushing the peasantry, and the Ukranians, at any cost. On ehigh official told a Ukrainian who later defected that the 1933 harvest “was a test of our strength and their endurance. It took a famine to show them who is master here. It has cost millions of lives, but the collective farm system is here to stay. We have won the war.”

It was an important learning experience not only for the peasantry, but for the police and Party officials. It prepared them for what was to follow.