In this scene from “Vory v Zakone†(1988), the corrupt procurator looks quickly in his law book and then tells the would-be complainant, “Sorry, but unfortunately there is no help here.” (Or something like that. I cannot follow the full conversation.) He’s obviously not a lawyer getting paid by the hour if he can make the determination that quickly, or maybe the Soviet laws were extremely clear and accessible if he could dispose of an issue that quickly. But what really caught my attention was the book cover.  The title was clearly shown just before the procurator closed the book in a show of sad resignation, thus enabling me to google for it.

Here it is: Soviet Law and the Citizen. You can buy your own set (there are two volumes) at ozon.ru.

One of my first reactions to the movie scene was to ask how people could respect the law if it has a book cover like that? That looks like a high school textbook from the 60s.

Here is an earlier version of Soviet Law and the Citizen. It’s more dignified, but still…

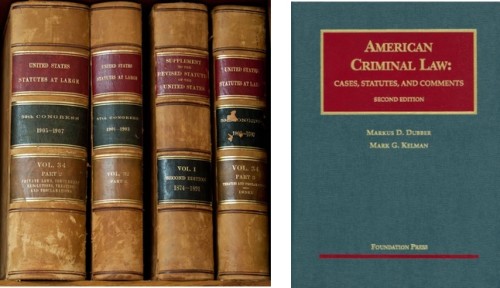

If you want people to respect the law, it needs to be bound in books like this. They lend gravitas and a sense of historical weight.

On the other hand, maybe historical weight is exactly what the Soviet government did not want, considering its type of revolutionary history.

I don’t know exactly what kind of effect the publisher of these laws was trying for, but one thing I’d wager is that any symbolism or connotation was intentional. So much of our own court system is intended to make an impression on the people — the architecture, the spacing and positioning of the courtroom elements, the judicial robes. It’s fun to look at Soviet movies (as well as photos in news articles about modern Russian court proceedings) and compare the two systems and speculate on what kind of effect each was intended to have on the participants. Since there are quite a few Russian movies with court scenes, this could be the subject of several blog articles to come.

I’m not sure what the filmmakers were thinking of when they made this car chase scene in “Vory v Zakone†(1988). Gangster #1 (played by Valentin Gaft) has his driver take off at high speed after Gangster #2, who tries to get away.

I’m not sure what the filmmakers were thinking of when they made this car chase scene in “Vory v Zakone†(1988). Gangster #1 (played by Valentin Gaft) has his driver take off at high speed after Gangster #2, who tries to get away. Gangster #1’s girlfriend, Rita, was in his car when he started, so after getting up to speed he stops the car to interrupt the pursuit and let her out, tell her he loves her (in none-too-speedy a fashion) and then resume the chase.

Gangster #1’s girlfriend, Rita, was in his car when he started, so after getting up to speed he stops the car to interrupt the pursuit and let her out, tell her he loves her (in none-too-speedy a fashion) and then resume the chase. Amazingly,Gangster #2 didn’t use the interruption to lose Gangster #1, because immediately thereafter Gangster Gaft sans girlfriend is is still on his tail, and the usual sort of mahem ensues (including running over a baby in a carriage).

Amazingly,Gangster #2 didn’t use the interruption to lose Gangster #1, because immediately thereafter Gangster Gaft sans girlfriend is is still on his tail, and the usual sort of mahem ensues (including running over a baby in a carriage).