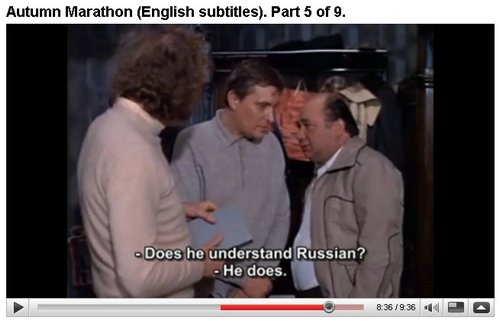

In this scene from Osenniy Marafon, the character played by Yevgeny Leonov (on the right) walks in on Buzykin (Oleg Basilashvili) and his guest, Bill Hansen. Leonov’s character doesn’t even notice Bill until he says two words in Russian (not his first language). Then there is a long silence while Leonov looks at him suspiciously, followed by an introduction (shown above).

Leonov then asks, “Does he understand Russian?”

Well, I thought it was funny. Bill knows more Russian than I do, but there was something about the way he sounded when he opened his mouth that made clear right from the start that he didn’t know the language very well. Was it the pronunciation? The way he spoke slowly and deliberately? Or was it the choice of words? I recognize the first word he said, but not the second, and can’t find it in any online dictionary or translator.

Whatever the case, I could see giving myself away that quickly, too, if I were ever to visit Russia and open my mouth to talk.

Speaking of a visit to Russia, I’ve been reading a wonderful travelogue on Crazyguyonabike.com. It’s “A Honeymoon to Remember” by Erin Arnold Barkley and Sam Barkley, who rode their bikes through a bit of Russia between Kazakhstan and Mongolia on a tour that’s still in progress several months later. Erin describes the arrival at Srotski:

We rode all afternoon, making it to near Srotski, birthplace of a guy I’d never heard of, Vasily Shukshin, but it seems like he was a big deal around the village: virtually every building had a sign like “Shukshin’s primary school” or “Shukshin’s mom’s house.” Anyway, Wikipedia tells me he was a famous Soviet playwright and director, and his monument on a hill sure provides stunning views of the surrounding countryside.

The name Vasily Shukshin didn’t ring a bell for me, either, so I looked him up and saw that I’ve already seen one movie in which he appeared in a minor role: Komissar.

An article about him at russia-ic.com had this intriguing information:

The film Kalina Krasnaya (aka The Red Snowball Tree) released in 1974 came as a mind-blow: there had been nothing of the kind in domestic cinema before. The story of a former prisoner who decides to break with the criminal world and live a peaceful country life holds a firm place in the gold Russian cinematography, as well as the majority of movies with Shukshin’s participation.

Vasili Shukshin died on October 2, 1974 during the filming of “Oni Srazhalis Za Rodinu” (aka They Fought for Their Country) of a heart attack. There are some suspicions he was poisoned.

Memocast has the film Kalina Krasnaya, but as far as I can tell nobody has produced any English subtitles for it. So it will probably have to wait until I learn more Russian. I haven’t yet found out whether there are English subtitles for any of Shukshin’s other films.

That travelogue on crazyguyonabike.com has some great photos, btw. Highly recommended.