So far I’ve watched up through part 5, and so far it’s great–one of the best I’ve seen. I wouldn’t have known how good it is based on the Wikipedia article about it, though:

The film received mixed reviews from critics. The entertainment magazine Variety referred to the film as “more off-putting than enthralling” and noted that while the film has been compared to the Academy Award–winning Burnt by the Sun, it lacked a main character that a viewer could identify with. Variety commented that Viktor’s personal struggles “[seemed] irrelevant” and criticized Petrenko’s “limited emotional repertoire”, as well as the poor acting of the remaining cast of characters.

I went to the Variety review that’s referred to and didn’t get any further enlightenment. I think the reviewer is nuts. The “off-putting” comment comes in this sentence:

For Western auds, however, pic’s oddly disjointed wedding of operatic emotionalism and cool aesthetic distance may prove more off-putting than enthralling.

The reviewer is perceptive in noting the contrast between “cool aesthetic distance” and emotionalism; however, so far I don’t see anything operatic about it. Maybe it gets operatic later. In any case, I happen to be one who finds the contrast enthralling. I’ve already gone back and watched some of the scenes over and over, even though I haven’t finished watching the whole thing yet.

I don’t know why it matters that there is not a main character to identify it, because there are several characters we quickly learn to care about: The General, Viktor, Vera — even Lida and the KGB guys. And there are other minor characters who are interesting, too. That’s what matters.

To mention Burnt by the Sun by way of comparison is goofy. Burnt doesn’t measure up to this one at all. It does have a central character — or should I say a central actor — Nikita Mikhalkov. But in his role as a retired military officer, I got no sense at all of why he would be admired and respected by the men who had fought under him. As usual, Mikhalkov played Mikhalkov. He just couldn’t pull off the character he’s supposed to play.

But here I am, contaminating a note about a good film with talk about an inferior one.

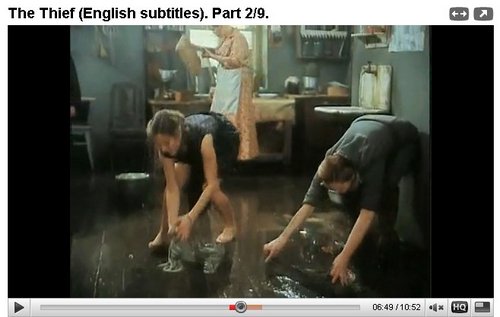

And poor acting? So far I haven’t seen any poor acting in this film. The screenshot above shows some great acting. The bad guy is a clean-cut young KGB officer who smiles easily, but who is doing some dastardly business in his interrogation of the General. Very realistic, IMO. Very seldom, i.e. almost never, do you see a movie that has guts enough to do that. Usually movies have to give the bad guys bad haircuts, bad complexions, and sinister mannerisms so you know they’re bad. But that’s not how the world works. The other KGB officer — the one who plays the General’s adjutant — has a little of the usual, but still it’s very subtly done.

The reviewer almost may have had a point about Igor Petrenko’s “limited emotional repertoire.” However, keep in mind that he’s a very young man. He’s playing the part of a young man very well, and there is more subtle variety to his behavior than you’re likely to get from a young Brad Pitt.

I wish I had the recording of Nature Boy that’s used in part 4 of the film. I wasn’t familiar with the song so had to google for information about it. I like the one on the film better than any version I’ve found on YouTube — even better than the Nat King Cole version I found there, though that one is pretty good. Who is singing in the film? The orchestration sounds like it comes from the late 40s or early 50s.

I see that Pavel Chukhraj, who directed the film, is also the person who made Vor. I’ll have to start paying attention to that name.