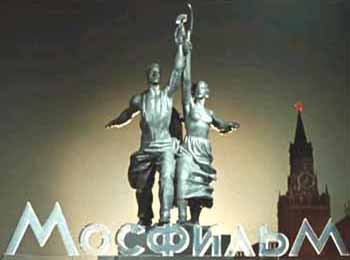

Tonight we finished watching Mimino, a 1977 Russian movie. (We hardly ever have time enough to watch one of these movies in one sitting.)

It’s a variation on the tale of the Country Mouse and the City Mouse, except that the country mouse is a Georgian aircraft pilot whose nickname is Mimino, the city is Moscow, and the country mouse ends up being friends with an Armenian truck driver.

I see (not from the movie) that Mimino means “sparrow hawk,” which gives me extra reason to like him. The name Macketai-meshe-kiakiak also means sparrow hawk — Black Sparrow Hawk, to be more exact. I’ve spent a lot of time bicycling and researching things related to the Sauk leader Black Hawk in the past 10 years. I’m not sure if a Georgian sparrow hawk is the same as an American sparrow hawk, though. The American one is also known as the American Kestrel (Falco sparverius).

The film was a great one for language learning, so as usual I have an excuse to watch it at least once more. There was also some Georgian spoken, of which I still understand not a syllable even though this is the 2nd movie for us in which that language is spoken.

One fascinating part was the way the judicial system was portrayed. I don’t expect it to represent the real workings of the Soviet system any more than American movies portray the real workings of our own system, but still, it presents a picture of how it was ideally supposed to work.

I say ideally because it’s obvious that this is yet another movie that dares not be critical of the police and judicial authorities, who are all good, virtuous, and competent. All that goodness and competence puts severe limits on the possibilities for comedy and suspense, but the movie manages to work with it.

I gathered that the trial system is more like the French or Roman system than the English/American adversarial one — which is not surprising.

When our protagonist met his court-appointed attorney, I thought I knew what came next. It usually means trouble for the defendant, whether it’s in the English or the Roman system. But this is a young woman who explains it’s her very first case and offers that he can ask for a different attorney. He declines, and puts himself in her hands. She works hard for our hero, doing extra detective work on his behalf, and in the end does a charming little dance upon exiting the court building, excitedly explaining to her waiting family that she got our hero off with just a small fine.

Who wouldn’t want a court system that worked that way, with cute young court-appointed attorneys to play Deus ex Machina and see that justice is done? But unfortunately, one realizes that there is no reward system to reinforce that kind of behavior, not in their system or in ours.

What one reads about now is articles like this one from the WSJ: “Living larger in the new Russia.” Vitaly Sarodubova and his wife support Putin wholeheartedly, even though things like this happen:

Vitaly was mugged walking back from visiting Svetlana in her concierge compartment one evening. He says a young couple he thought was waiting for the bus asked him for a cigarette. As he reached to get one, he was hit from behind.

He wasn’t carrying his cell phone, he says, so all the thieves got was the 800 rubles he had in his pocket. When he stumbled home, he didn’t call the police or a doctor. “The police will just accuse me of something I’m not guilty of,” he says.

They’re obviously not comparing this to an earlier time when the police and judicial authorities worked as portrayed in this movie. But the fact that Russian in the 1970s had the ideal that it ought to work as portrayed in this movie was new information for me.