There is an amazing article by Josh Levin at Slate.com: “How is America Going to End? Five steps to totalitarian rule.” It makes a lot of good points, even going to the trouble of pointing out FDR’s authoritarian tendencies and abuses of power during the 1930s.

The truly amazing part is how it managed to put out so many words without once mentioning Barak Obama’s actions in the direction of totalitarianism. It mentions Bush & Cheney quite a bit, and gives a fairly balanced account of what they did and didn’t do in the totalitarian direction. Richard Nixon gets a mention. But there is not a word about Barak Obama’s new detention policies that go farther than Bush’s ever did, or his politicization of the Justice Department, or his takeovers and attempted takeovers of various sectors of our economy, or his intolerance of dissenting viewpoints.

How could anyone who is not a partisan hack write such an otherwise balanced account without mentioning our current President, I wondered.

Then I got to thinking that it’s not so unusual after all. Slate is well known as a leftwing magazine. Young leftwingers are not very tolerant these days. If Levin wants to be able to be allowed to work, breed, and not have others treat him like a pariah, it’s probably not something he dares to talk about directly. He needs to talk in parables and circumlocutions to get his point across.

It’s not unlike in movies made in Soviet Russia. In those I’ve seen there is (to me, at least) a surprising amount of social commentary that would probably not have got past the censors if they had discussed the topics directly. So a comedy like Kin-Dza-Dza could be criticial of a government infested with bribe-takers and abusers of power — if the action took place on another planet.

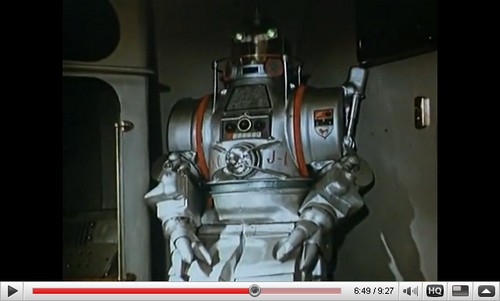

That movie is probably not the greatest example, because Kin-Dza-Dza was released in 1986 when the Soviet Union was already much more open than it had been previously. But I happen to have the movie handy, including the above part where our heroes have just reached the point when they cannot take it anymore and have decided to fight back, starting by taking down the police officer who is helping himself to bribes.

Tarkovsky’s Solaris is probably a better example. It came out in 1972, a very different time, and it, too, got by with a lot by putting the setting on another planet. That way any messages wouldn’t strike too close to home.

Another example is in the 1973 TV series that Myra and I are currently watching: “Seventeen Moments in Spring”, which takes place in Nazi Germany. The English subtitles for the narrator for Göring’s words at the point of the above screenshot say, “Our concentration camps are humane instruments to save the enemies of national-socialism. If we don’t put them in camps, there will be a mob law. In such way, they’ll be completely reformed and realize our rightness”. Even in 1973 it was probably easier and more effective to talk about that than about the GULAG system of corrective labor from the same World War II period, which had very similar methods and purposes.

I’m not sure if the movie was really intended as social commentary, though. So far what I’ve seen of it is a very patriotic movie that doesn’t seem to be getting in digs at problems that include the producers’ own country. But I wonder if a viewer, perhaps living in the same household with former inmates from the GULAG, could help but think about how their own country once did such things, too.

This sort of indirect system of social commentary is of course not just a feature of Soviet Russia. Authors and producers in other countries have sometimes had to approach issues indirectly, too. And if you consider the type of people who usually read Slate, it’s probably something that happens in our country, too. The Josh Levin article may very well be an example.

Late note:Â Also cross-posted to The Reticulator