I’ve started to watch Repentance (Pokayanie). Unfortunately, the language spoken is Georgian, not Russian. Nothing wrong with that, but I understand not a syllable of Georgian, so I’m listening to the Russian overdub while reading English subtitles. I’ve had a little practice in watching movies this way, but not enough to be entirely used to it.

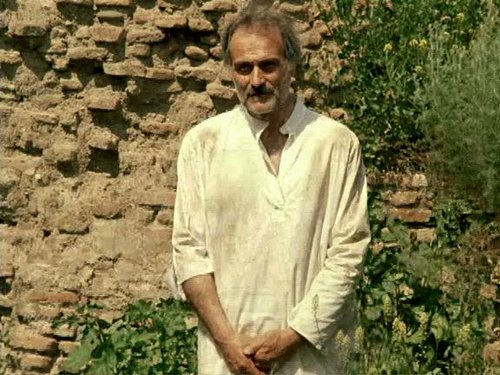

I got about as far as the above scene, at about 41:50. A delegation of people has come to the mayor (a Hitler, Stalin, Mussolini character) complaining that the scientific experiments are destroying the church. The mayor is all smiles and accommodation, and then asks the young father in the delegation:

You live on the town square in a two-story house, don’t you? During the ceremony a girl was blowing soap-bubbles from the window. Was that your apartment?

Yes.

I see everything, I notice everything. So beware of me, be careful.

And if he saw that, he of course also saw what isn’t stated, that the father pulled the girl back and shut the window.

(It reminds me that in the early days of the Clinton administration it was announced that the President would be coming to Battle Creek. On a local online forum I said it would be a good time to bring the family inside to safety, shutter the windows and lock the doors until he had gone. I was surprised at the number of people who were extremely offended that I would talk that way. Maybe they had been characters in this same movie, which btw was released in 1987, after being suppressed for a few years.)

The mayor notices everything, but during that ceremony, nobody dared spoil the festivities by noticing that workmen had accidentally broken a water main which was drenching the speakers who were honoring the mayor, as well as the typist-clerk who kept on typing.

It kind of reminds me of how nobody is supposed to notice the government policies that brought on our current financial crisis, and that we are expected to respond by enacting more of the same.

There is very little about this movie on Wikipedia or any of the usual places. Anna Lawton wrote about it in one of her books, but I’ve already forgotten much of what she had to say. After I finish watching I’ll go back and find what she had said.

I understand it’s the third in a trilogy. I suspect I’ll want to watch the two movies that preceded it, too.