My crusade to outlaw television in public places is not going very well — certainly not as well as other crusaders’ measures to outlaw smoking.

I figured it would probably be an issue when I took my wife in for outpatient surgery this morning. But I’ve been able to deal with it in the past. I usually complain politely, or just find a place where I can turn off an offending television and wait in relative quiet. Last time I was hospitalized myself I made my opinions known, and got paired with a roommate who was willing to leave the thing off. A big HMO-type dentist place I used to go to wasn’t so bad — the large waiting room was divided into two parts, TV and non-TV. It was somewhat like restaurants that have both non-smoking and smoking sections; some noise still ended up in the non-TV section. But it was tolerable.

Last time my wife was hospitalized, she was paired with a roommate who refused to turn the thing off. My wife couldn’t get any rest. The thing was so loud her physician couldn’t talk to her. The roommate refused the physician’s requests to turn the thing down; which led to my wife getting moved to a private room.

Anyhow, this morning we ended up in a new, improved waiting room. But now there are even more televisions, not fewer. Big, flat-screen television screens were everywhere. There was no getting away from them. After my wife was taken to surgery prep, I tried all corners of the room, but couldn’t get away from the sounds of idiocy coming from CNN or whatever was on. Finally I found a chair in a location that was a little less bad. I sat and held my hands over my ears while I read Anna Lawton’s book, “Kinoglasnost”. Just cupping the hands over the ears doesn’t quite work, but I can block out the sounds well enough by pushing on the tragus (I think that’s the term) — not just holding it still but pressing on it repeatedly and continuously. I had to take my hands off to turn the pages, but occasional blasts of noise like that are tolerable.

I tried to resume that routine after my wife went to surgery, but finally my arms got tired, and I asked the person at the desk if there was any place to get away from the televisions. I didn’t want to get so far away that I wouldn’t be around when the surgeon came out to talk to me; finally, I decided to just stand in the hallway outside the waiting room and read. If I can walk around a little, and if I stand straight, I can stand up and read for long periods, like I did once outside a jury assembly room. That worked OK, and a person at the desk came and got me when the surgeon came. (My wife’s surgery went very well — we are thankful for that. Maybe they don’t have television blaring in the operating room.)

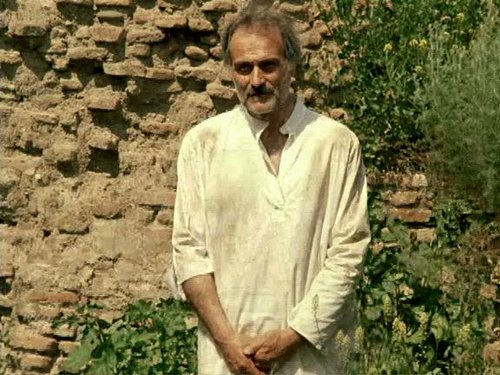

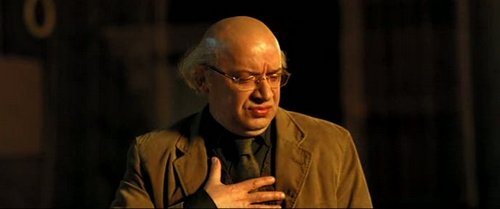

I suppose a person could get used to the television noise, but I don’t care to. I’m not sure, but I think the purpose of all that television is to turn peoples’ brains to jelly so they’ll vote Democratic. In looking around the waiting room to see if it made anyone else unconfortable, all I saw was people — even elderly people — looking at the idiots on the screen. Maybe it was because I was reading about Russian movies, but at one point while looking at the people I was reminded of a scene from Gruz 200. It’s pretty close to the one in the above screenshot.

The old woman spends her time watching the TV and drinking vodka. Some reviewers say she’s senile; but really, she’s worse than that. The movie is one of the filthiest, most disgusting I’ve ever seen — but there is an important point to it, which I won’t go into here. The son is a police chief, and is also a crook and rapist. He discusses the rapings with his mother, who has a perverted solicitude for her son. She tries to convince the girl to like it. But mostly, she just watches the television, oblivious to the evil and violence going on in her house except for those times when she is facilitating it.

I wondered if that’s what all the television would do to us someday. It also occurred to me that we’re coming to be more like North Korea, where it is said radios in public places are constantly blaring at people. You can’t get away from them there, either.

My kids give me a bit of a hard time about my inability to stand radio or TV noise, because when I watch Russian movies I tend to crank the volume up. It’s true — I do — mostly because I can make out unfamiliar sounds better that way.

And I do watch some television. Some years I watch the baseball playoffs and World Series, though maybe the last time was 4-5 years ago. And I watch the NCAA basketball tournament with my wife. When we do this I want to listen, not just watch. But even so, it is a blessed relief when the games are over and we turn the TV off. It’s as if a oppressive weight is lifted off my head, and I can breath free again. I wish more people would find out how wonderful the sounds of silence can be.

But it doesn’t have to be silence. While my wife was recovering after surgery, a one-year-old baby nearby was bawling its head off. Some people seemed to be bothered by it, but to me that sound is almost like music in comparison to television. Crying is not as good as laughter, but either way, it was the sound of a real person, not a TV idiot. I hope we don’t create a TV-drenched world for that baby — like that apartment in Gruz 200.